On Monday, April 28, 2025, residents on the Iberian Peninsula, specifically in Spain and Portugal, experienced a widespread power blackout affecting critical infrastructure including mobile communications, ATMs and public transportation.

While the exact cause of the blackout is still under investigation and only partial data and facts have been disclosed to the public, this incident raises questions about the power grid, blackout causes, and the likelihood of a similar event in the United States.

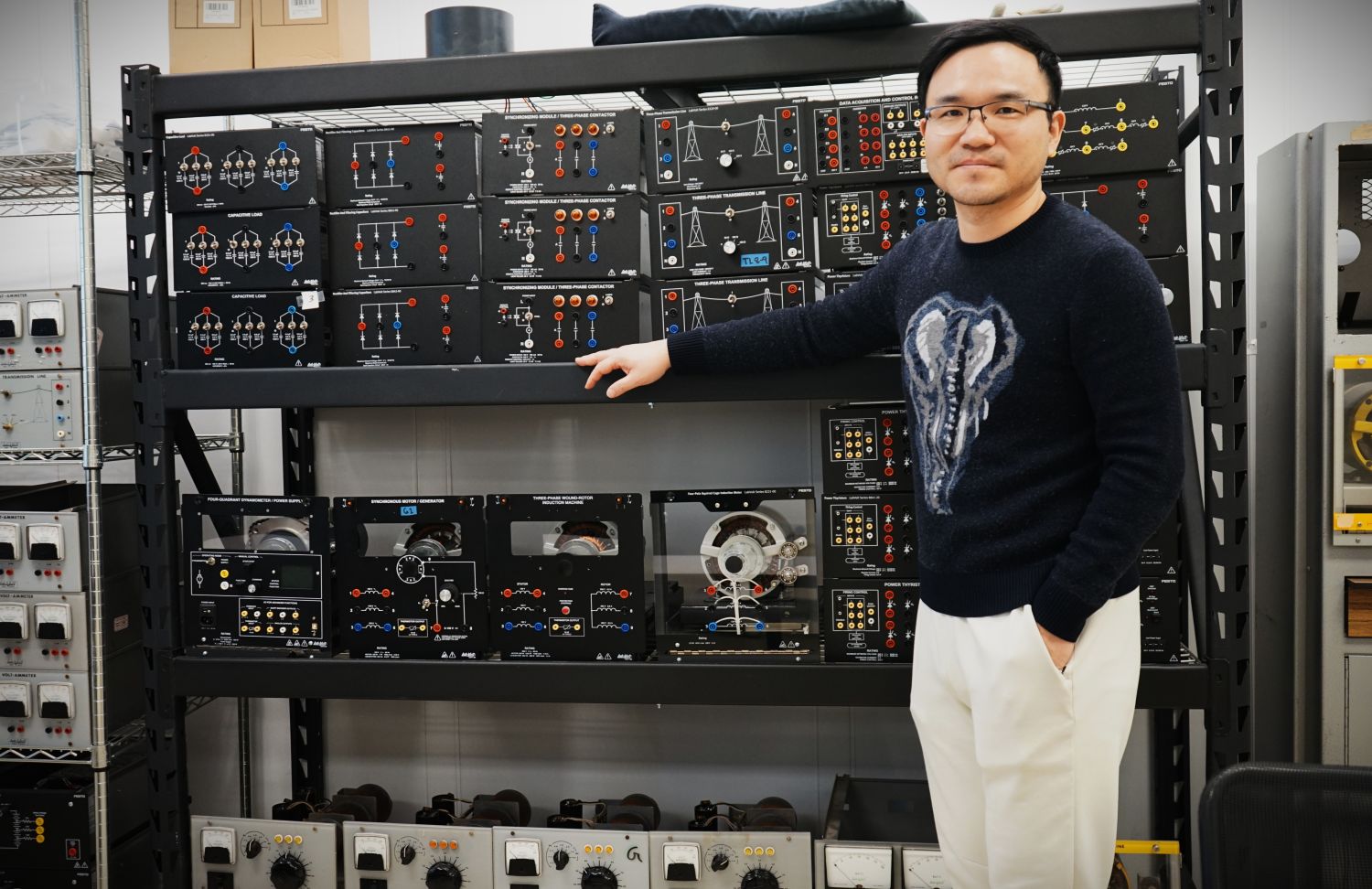

The College of Engineering’s Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Liang Du, PhD sheds light on the intricacies of a power blackout.

College of Engineering: What causes a power blackout?

Liang Du, PhD: Power grids operate based on the balance of real-time supply and demand. Overgeneration or over demand could trigger protection devices such as digital relays, which are deployed throughout power grids to protect critical equipment from damage and also protect civilians from exposure to high voltage. Depending on the size, location, time and root cause of faults, power grids could experience contained, small-scale outages or uncontrolled, wide-area outages. The latter is typically called a blackout.

The exact cause of the recent Iberian blackout remains unknown. Within 2 seconds, two major events (loss of generation, which are called contingencies) in southwest Spain, which is a rare event, caused cascading faults in several seconds (frequency decrease and voltage increase were observed in Spain and Portugal) and the power grid collapsed.

College of Engineering: In the case of the blackout in Europe, people in several countries were affected. How do power blackouts affect multiple countries or states?

Liang Du, PhD: Power grids are typically interconnected with the capability to support each other. When the Iberian outage occurred, Iberia lost its electrical connection to France. The overflow limit was reached and thus tripping of protections occurred. Because of the protection relays deployed in power grids, the fault was contained as fast as possible with as small range as possible, i.e., blackouts were not propagated outside of Iberia since France disconnected from the Iberia grid in time.

Sometimes, the protection system or system operators would open electrical links to isolate the fault and prevent other areas from cascading outages. If this is not done soon enough, the outage could propagate and impact many countries or states.

A similar event was the Northeast blackout of 2003, which was also a widespread power outage throughout parts of the Northeastern and Midwestern US. A software bug existed in General Electric’s alarm system led to cascading loss (started in New York) of transmission and generation capability and eventually affected an estimated 55 million people.

College of Engineering: Are some areas more susceptible than others to blackouts?

Liang Du, PhD: Indeed. Take the 2021 Texas blackout for example, which left nearly 10 million people in the United States and Mexico without electricity/heat/water for days and cost over $195 billion in property damage and many lives, according to the 2021 Winter Storm URI After-Action Findings Report. Data shows that high minority areas are more likely to experience blackouts. This aligns with consistent findings that socioeconomic statuses play a key role in communities’ situational preparedness against disruptions. Low-income groups are more likely to live with widespread utility hardship and lower-quality housing.

College of Engineering: How long can it take for power to be restored?

Liang Du, PhD: It depends. It could take hours or days, or even longer depending on the availability of backup resources, black-start capabilities, and situation awareness such as how many transmission lines in which regions were impacted and what other resources are still available to the system operators to dispatch. Some areas might have sufficient backup generators or reserves that can get online in 15 to 30 minutes, which some other areas may be isolated since some major transmission lines or substations were damaged.

College of Engineering: What can be done to prevent these blackouts?

Liang Du, PhD: It is a question of cost and risks. Most of the power grid operators in the world adopt the so-called “N-1 contingency” criteria, which means that the power grid should be able to ride through one major failure. What happened in Iberia was actually N-2 since 2 major failures happened only 1.5 seconds away from each other. Power grids are not prepared for that. A similar blackout was the 2019 UK outage, in which lightning strikes caused one major wind farm to trip while almost simultaneously another thermal generator was also taken offline. If we can invest more to operate power grids with more synchronized resources, blackouts might be prevented. However, the cost would be a major concern. Ideally, system operators would like to have as much reserves or backup generation capability as possible. However, generation units need to be paid, no matter they are being used or not, which are known as their opportunity cost. The amount of wholesale payments made to ancillary services, such as spinning and primary reserves, have been increasing very fast in recent years, which contributed to the increasing electricity price.

Du received an NSF CAREER Award in 2023 for energy research. His current research focuses on using distributed energy resources and electric vehicles in future clean power grids with a goal to enhance grid resilience.

Sources:

“2021 Winter Storm URI After-Action Review Findings Report City of Austin & Travis County.” Austin: City of Austin Texas, 2021. https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/HSEM/2021-Winter-Storm-Uri-AAR-Findings-Report.pdf

Naishadhamilson, Sumanph, and Joseph Wilson. “Power Returns to Spain and Portugal. The Outage’s Cause Remains a Mystery.” Associated Press, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/spain-portugal-power-outage-electicity-533832bb4ceae92eaa68c23dc0b5db18.

Sullivan, Brian, and Naureen Malik. “5 Million Americans Have Lost Power From Texas to North Dakota After Devastating Winter Storm.” TIME, 2025. https://time.com/5939633/texas-power-outage-blackouts/.

“Why Did the Lights Go Out in Spain and Portugal? Here’s What We Know.” New York Times, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/28/world/europe/spain-portugal-power-outage-what-we-know.html .